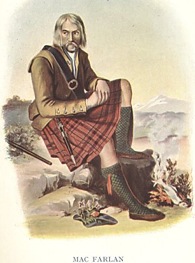

Clan MacFarlane

Clan MacFarlane WebsiteHistory of the Name

MacFarlane comes into being because Gaelic grammar requires changes within a word to show possession. A "P" is softened to a "Ph", and an "i" is added to the last syllable. In this way, "son of Parlan" comes from "Mac" (son) "Pharlain" (of Parlan). All the variant spellings came about when scribes (usually not Gaelic speaking) tried to write the name as they heard it. No variants of MacPharlain are shown as they are derived from the clan’s name.

The list to the side is a partial list of the surnames associated with Clan MacFarlane. To conserve space, only Mac forms are shown. Mc and M’ are scribal abbreviations, and therefore should be considered as included. All spellings derivable from the names and variants shown below should be considered as included also.

Tartans

Tartan is a living textile art form that began in the Highlands of Scotland about the same time that Europeans discovered both their own minority cultures and the New World. Over the centuries the " Pride o' Tartan" has grown while the exodus of Scots to new homes throughout the world continues even today. Millions throughout the world look to Scotland as their point of cultural heritage. Tartan is the living, visible symbol of this identification.

These are the tartans of the Clan MacFarlane

The Modern tartan is a general use tartan. This tartan in its different forms of "ancient" and "muted and weathered" can be used for all occasions, whereas the Hunting tartan in all of its forms is generally used for "everyday" wear. However, to wear the hunting tartan for semi formal occasions would probably not be inappropriate as it is a favorite of many MacFarlanes.

The MacFarlane 'Dress Tartan" (World Register 659) is a handsome tartan of white background with blue and red over stripes. Dress tartans are designed for fancy dress occasions. Remember that almost all of the tartans we know of today were the designs of the Victorian Scottish Weavers developed during the1800's. They were not worn during the time of William Wallace or Robert the Bruce. The MacFarlane "Black and White" is probably an "Evening Sett", the dress form of the Lendrum-

MacFarlane Clan Tartan (The MacFarlane Black and Red (World Register 1190)). Although often referred to as a mourning sett it has none of the characteristics of this sett, i.e. dark background with a white over stripe. The brightness of the sett would probably make it a little bold for a funeral. This tartan may have been worn by women as an arisaid, a type of cloak worn by women from the 17th to the 19th century, but the pattern would have been much larger and brighter.

The reasons for the names "Modern" and "Ancient" involves a bit of history. During Victorian times, it was stylish to use very dark dyes, where the blues were almost black, the greens were forest-green instead of kelly-green, and so on. This made for some very somber tartans and also made recognition harder in many cases. When they finally decided to use lighter colors, however, they came up with the following reason: They argued that the old dyes and darker colors could not have been produced in the "old days", so they called the lighter, more natural colors "ancient" and the darker colors "modern." As these tartans probably did not exist in the "old days" this becomes an exercise in good marketing. Whatever tartan you choose wear it with pride as you are a member of the MacFarlane Family. [

More MacFarlane tartans]

Clan History

Of the clan Macfarlane, Mr Skene gives the best account, and we shall therefore take the liberty of availing ourselves of his researches. According to him, with the exception of the clan Donnachie, the clan Parlan or Pharlan is the only one, the descent of which from the ancient earls of the district where their possessions were situated, may be established by the authority of a charter. It appears, indeed, that the ancestor of this clan was Gilchrist, the brother of Maldowen or Malduin, the third Earl of Lennox. This is proved by a charter of Maldowen, still extant, by which he gives to his brother Gilchrist a grant "de terris de superiori Arrochar de Luss"; and these lands, which continued in possession of the clan until the death of the last chief, have at all times constituted their principle inheritance.

But although the descent of the clan from the Earls of Lennox be thus established, the origin of their ancestors is by no means so easily settled. Of all the native earls of Scotland, those of this district alone have had a foreign origin assigned to them, though, apparently, without any sufficient reason. The first Earl of Lennox who appears on record is Aluin comes de Levenox, who lived in the early part of the 13th century; and there is some reason to believe that from this Aluin the later Earls of Lennox were descended. It is, no doubt, impossible to determine now who this Aluin really was; but, in the absence of direct authority, we gather from tradition that the heads of the family of Lennox, before being raised to the peerage, were hereditary seneschals of Strathearn, and bailies of the Abthanery of Dull, in Athole. Aluin was succeeded by a son of the same name, who is frequently mentioned in the chartularies of Lennox and Paisley, and who died before the year 1225. In Donald, the sixth earl, the male branch of the family became extict. Margaret, the daughter of Donald, married Walter de Fassalane, the heir male of the family; but this alliance failed to accomplish the objects intended by it, or, in other words, to preserve the honours and power of the house of Lennox. Their son Duncan, the eighth earl, had no male issue; and his eldest daughter Isabella, having married Sir Murdoch Stuart, the eldest son of the Regent, he and his family became involved in the ruin which overwhelmed the unfortunate house of Albany. At the death of Isabella, in 1460, the earldom was claimed by three families; but that of Stewart of Darnley eventually overcame all opposition, and acquired the title and estates of Lennox. Their accession took place in the year 1488; upon which the clans that had been formerly united with the earls of the old stock separated themselves, and became independent.

Of these clans the principal was that of the Macfarlanes, the descendants, as has already been stated, of Gilchrist, a younger brother of Maldowen, Earl of Lennox. In the Lennox charters, several of which he appears to have subscribed as a witness, this Gilchrist is generally designated as frater comitis, or brother of the earl. His son Duncan also obtained a charter of his lands from the Earl of Lennox, and appears in the Ragman's roll under the title of "Duncan Macgilchrist de Levenaghes." From a grandson of this Duncan, who was called in Gaelic Parlan, or Bartholomew, the clan appears to have taken the surname Macfarlane; indeed the connection of Parlan both with Duncan and with Gilchrist is clearly established by a charter granted to Malcolm Macfarlane, the son of Parlan, confirming to him the lands of Arrochar and others; and hence Malcolm may be considered as the real founder of the clan. He was succeeded by his son Duncan, who obtained from the Earl of Lennox a charter of the lands of Arrochar as ample in its provisions as any that had been granted to his predecessors; and married a daughter of Sir Colin Campbell of Lochow, as appears from a charter of confirmation granted in his favour by Duncan, Earl of Lennox. Not long after his death, however, the ancient line of the Earls of Lennox became extinct; and the Macfarlanes having claimed the earldom as heirs male, offered a strenuous opposition to the superior pretensions of the feudal heirs. Their resistance, however, provided alike unsuccessful and disastrous. The family of the chief perished in defence of what they believed to be their just rights; the clan also suffered severely, and of those who survived the struggle, the greater part took refuge in remote parts of the country. Their destruction, indeed, would have been inevitable, but for the opportune support given by a gentleman of the clan to the Darnley family. This was Andrew Macfarlane, who, having married the daughter of John Stewart, Lord Darnley and Earl of Lennox, to whom his assistance had been of great moment at a time of difficulty, saved the rest of the clan, and recovered the greater part of their hereditary possessions. The fortunate individual in question, however, though the good genius of the race, does not appear to have possessed any other title to the chiefship than what he derived from his position, and the circumstances of his being the only person in a condition to afford them protection; in fact, the clan refused him the title of chief, which they appear to have considered as incommunicable, except in the right line; and his son, Sir John Macfarlane, accordingly contented himself with assuming the secondary or subordinate designation of captain of the clan.

From this time, the Macfarlanes appear to have on all occassions supported the Earls of Lennox of the Stewart race, and to have also followed their banner in the field. For several generations, however, their history as a clan is almost an entire blank; indeed, they appear to have merged into mere retainers of the powerful family, under whose protection they enjoyed undistirbed possession of their hereditary domains. But in the sixteenth century Duncan Macfarlane of Macfarlane appears as a steady supporter of Matthew, Earl of Lennox. At the head of three hundred men of his own name, he joined Lennox and Glencairn in 1544, and was present with his followers at the battle of Glasgow-Muir, where he shared the defeat of the party he supported. He was also involved in the forgeiture which followed, but having powerful friends, his property was, through their intercession, restored, and he obtained a remission under the privy seal. The loss of this battle forced Lennox to retire to England; whence, having married a niece of Henry VIII, he soon afterwards returned with a considerable force which the English monarch had placed under his command. The chief of Macfarlane durst not venture to join Lennox in person, being probably restrained by the terror of another forfeiture; but, acting on the usual Scottish policy of that time, he sent his relative, Walter Macfarlane of Tarbet, with four hundred men, to reinforce his friend and patron; and this body, according to Holinshed, did most excellent service, acting at once as light troops and as guides to the main body. Duncan, however, did not always conduct himself with equal caution; for he is said to have fallen in the fatal battle of Pinkie, in 1547, on which occasion also a great number of his clan perished.

Andrew, the son of Duncan, as bold, active and adventurous as his sire, engaged in the civil wars of the period, and, what is more remarkable, took a prominent part on the side of the Regent Murray; thus acting in opposition to almost all the other Highland chiefs, who were warmly attached to the cause of the queen. He was present at the battle of Langside with a body of his followers, and there "stood the Regent's part in great stead"; for, in the hottest of the fight, he came up with three hundred of his friends and countrymen, and falling fiercly on the flank of the queen's army, threw them into irretrieveable disorder, and thus mainly contributed to decide the fortune of the day. The clan boast of having taken at this battle three of Queen Mary's standards, which, they sau, were preserved for a long time in the family. Macfarlane's reward was not such as afforded any great cause for admiring the munificence of the Regent; but that his vanity at least might be conciliated, Murray bestowed upon him the crest of a demi-savage proper, holding in his dexter hand a sheaf of arrows, and pointing with his sinister to an imperial crown, or, with the motto, “This I'll defend." Of the son of this chief nothing is known; but his grandson, Walter Macfarlane, returning to the natural feelings of a Highlander, proved himself as sturdy a champion of the royal party as his grandfather had been an uncompromising opponet and enemy. During Comwell's time, he was twice besieged in his own house, and his castle of Inveruglas was afterwards burned down by the English. But nothing could shake his fidelity to his party. Though his personal losses in adhering to the royal cause were of a much more substantial kind than his grandfather's reward in opposing it, yet his zeal was not cooled by adversity, nor his ardour abated by the vengeance which it drew down on his head.

Although a small clan, the Macfarlanes were as turbulent and predatory in their way as their neighbours the Macgregors. By the Act of the Estates of 1587 they were declared to be one of the clans for whom the chief was made responsible; by another act passed in 1594, they were denounced as being inthe habit of committing theft, robbery, and opression; and in July 1624 many of the clan were tried and convicted of theft and robbery. Some of them were punished, some pardoned; while others were removed to the highlands of Aberdeenshire, and to Strathaven in Banffshire, where they assumed the names of Stewart, M'Caudy, Greisock, M'James, and M'Innes.

Of one eminet member of the clan, the following notice is taken by Mr Skene in his work on the Highland of Scotland. He says, "It is impossible to conclude this sketch without alluding to the eminent antiquary, Walter Macfarlane of that ilk, who is as celebrated among historians as the indefatigable collector of the ancient records of the country, as his ancestors had been among the other Highland chiefs for their prowess in the field. The family itself, however, is now nearly extict, after having held their original lands for a period of six hundred years.

Of the lairds of Macfarlane there have been no fewer than twenty-three. The last of them went to North America in the early part of the 18th century. A branch of the family settled in Ireland in the reign of James VII, and the headship of the clan is claimed by its representative, Macfarlane of Hunstown House, in the county of Dublin. The descendants of the ancient chiefs cannot now be traced, and the lands once possessed by them have passed into other hands.

More Clan History

[

From Electric Scotland] | [

From the Clan MacFarlane website]